By Franklin De Vrieze, Senior Governance Adviser, Westminster Foundation for Democracy

As parliaments start to pay more attention to their responsibility to monitor the extent to which the laws they have passed are implemented as intended and have the expected impact, Post-Legislative Scrutiny (PLS) is emerging as a new dimension within the oversight role of parliament. In my previous blogpost, I have elaborated on the rationale for parliaments conducting Post-Legislative Scrutiny, highlighting concrete examples of how parliaments have conducted ex-post review of legislation. In this blogpost, I will analyse the structures, procedures and methodologies shaping the ability of parliaments in Europe to conduct PLS, outlining a categorization of their institutional approaches.

As the involvement of parliaments in the ex–post stage of law making remains under-theorised, the Westminster Foundation for Democracy has just released a new publication, providing an analysis of the main rules, practices and trends on PLS in Europe, focusing on the experience of seven national parliaments: Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK.

Parliaments in Europe follow different approaches in conducting PLS. To explain how PLS progresses in parliament, the first contextual factor is its legal basis. In some cases, PLS by parliament is based directly in the Constitution, such as in France, Sweden and Switzerland. In other cases, PLS by parliament finds a legal basis in the oversight role of parliament and its Rules of Procedure.

Apart from the legal basis, recent research by the LUISS Guido Carli University stipulates that the approach of PLS depends on several main variables.

The first variable affects the parliament’s internal organisation regarding PLS, i.e. the identification of the relevant (internal or external) units responsible for the preliminary fact-finding and analytical activity whose aim is to evaluate the effects of implementing a single piece of legislation or a selected public policy based on one or more laws. This variable shows two main options. One consists of engaging external independent institutions or agencies with specific knowledge and experience in the field of policy evaluation and impact assessment (for instance, in Germany). The alternative is establishing new administrative units in parliaments in order to develop an autonomous expertise on legislative impact assessments (for instance, in Italy and Switzerland).

The second variable draws on the methods for identifying and selecting relevant pieces of legislation to be scrutinised. The selection issue raises several alternative options. The first affects the object of the scrutiny or evaluation, whether it is a single piece of legislation or all legislation relevant to a selected policy. The former hypothesis usually occurs when a review or sunset clause is set in the legislative act, tasking parliament to verify that the act is correctly implemented and that expected outcomes are fulfilled. The latter hypothesis is instead locating the object of PLS in the implementation of a selected policy through different acts. This approach is more consistent with the better regulation standards promoted by the OECD and by the EU.

The third variable identifies the scope of PLS, interpreted as a purely legal dimension or also comprising instances of impact assessment. In the latter case, different methodologies for evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of the law may be applied. In the first instance, the review only covers the monitoring of law enactment. Its aim is to check whether the implied regulations or administrative instructions have been approved, whether all the legal provisions have been brought into force, and what judicial interpretations are provided by the courts. In the second instance, parliament’s scrutiny comprises forms of ex-post policy evaluation and impact assessment.

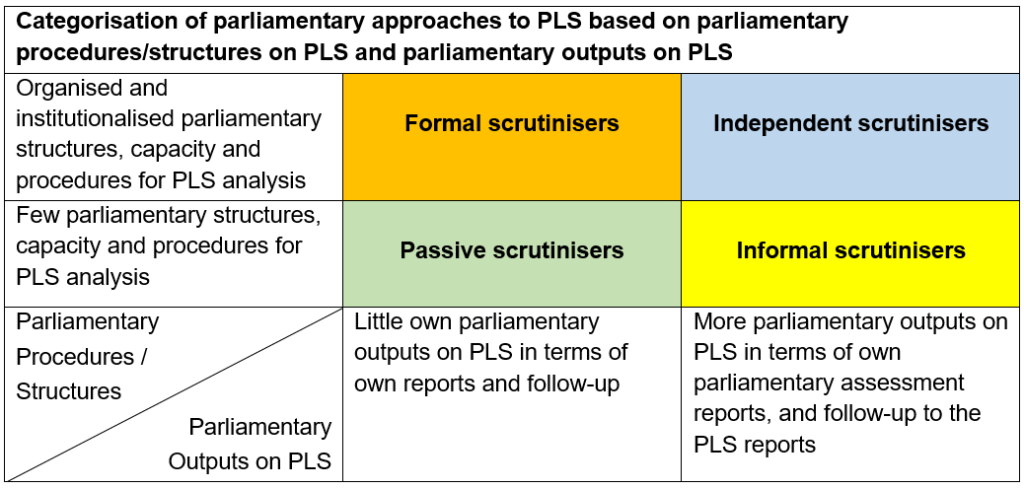

In the new WFD publication, I have analysed the structures, procedures and methodologies shaping the ability to conduct PLS in the seven parliaments. I have analysed these parliaments against four different categories of parliamentary approach to PLS: passive scrutinisers, informal scrutinisers, formal scrutinisers and independent scrutinisers. These four categories relate to the two main axes of analysis: the extent of parliamentary procedures and structures on PLS and the extent of parliamentary outputs on PLS.

In the ‘basic’ approach to PLS, parliaments as passive scrutinisers limit their role to the assessment of the scrutiny conducted by governmental bodies or external agencies. This ‘passive’ approach to PLS implies that the parliament does not directly engage in monitoring legislative implementation and in ex-post impact assessment on its own, as it relies on reports and evaluations produced by the government or independent agencies. Parliaments as passive scrutinisers have few parliamentary structures, capacity and procedures for PLS analysis and have few of their own parliamentary outputs on PLS in terms of their own reports and follow-up. Since most countries lack a strong parliamentary tradition in respect of ex-post impact assessment, scrutinising external reports and evaluations is the easiest and most common way to engage in PLS.

When parliaments decide to engage in a more proactive approach to PLS that goes beyond the mere assessment of the scrutiny activity of governmental bodies or external agencies, it requires assigning existing administrative parliamentary structures – such as research or evaluation units – to provide ex-post analysis of legislative implementation and impact assessment. The development of an internal scrutiny capacity offers parliaments autonomous resources in the fulfilment of the legislative scrutiny, additional to those offered by the government and other external structures. Parliaments falling within this category are considered ‘informal’ scrutinisers insofar as the connection with the parliamentary procedures is non-systematic. This means that there are no identified or established criteria or triggers to select legislation for PLS review, but it is decided on an as-needed basis.

Parliaments as formal scrutinisers have more developed structures and procedures on PLS but are still weak in terms of outputs and follow up. In this approach, the information gathering and analysis prior to PLS inquiries may not only be fulfilled by certain ‘traditional’ administrative structures – such as research and documentation units – but there is also the possibility to establish a newly dedicated PLS unit or legislative impact department, adding strength to the scrutiny capacity of parliament. PLS is thus vested in specific parliamentary administrative departments or units assigned to conduct PLS.

In the most ‘advanced’ approach, parliaments address PLS in an independent and highly institutionalised manner. There are specific administrative structures and committees assigned to conduct PLS. Based on their own criteria, triggers and priorities, parliament and its committees decide independently which laws to select for PLS. Parliament has a more proactive approach in identifying sources of analysis. Parliaments as independent scrutinisers are strong in terms of structures and procedures as well as in terms of outputs and follow up.

The four categories have been conceptualized according to an incremental logic how much capacity and independence of judgement the parliament can express in the fulfilment of this function. The categorisation in four categories aims to recognise the complexity of parliamentary institutionalisation in the area of PLS.

The following chart visualizes the four categories along the two axes of analysis: the extent of parliamentary procedures and structures on PLS and the extent of parliamentary written outputs on PLS. The vertical axis refers to the parliamentary structures, from few to more structures and procedures. The horizontal axis refers to the parliamentary outputs, from little own parliamentary written outputs and follow up to more parliamentary outputs and follow up.

The case-studies as analysed in detail in the publication indicate that the federal parliament of Belgium can be considered a passive scrutiniser in PLS. The federal parliament of Germany and the parliament of Italy can be considered informal scrutinisers. The national parliaments of Sweden and France can be considered formal scrutinisers in PLS. The Westminster parliament in the UK and the federal parliament of Switzerland can be considered independent scrutinisers in PLS.

As PLS is part of the oversight function that parliaments exercise with respect to the executive, PLS can be structured as a parliamentary duty with the specific purpose of supporting parliament’s engagement in impact assessment and ex-post evaluation. The case-studies highlight that parliaments’ involvement in this sphere might be supported either by ‘administrative’ strategies, such as the strengthening of the documentation and evaluation capacity of parliaments or by ‘political’ strategies focused on the reinforcement of parliaments’ influence on governments in the ex post stage. The case-studies demonstrate that PLS has been positively included in daily parliamentary practices, in different ways and according to different procedures.